What do you do if you’re the U.S. government and you’re short on (don’t have enough) money? You just print it, of course.

What do you do if you’re the U.S. government and you’re short on (don’t have enough) money? You just print it, of course.

During the U.S. Civil War (1861 to 1865), the federal (national) government was nearly broke (without any money). Before 1861, the U.S. did not have paper money as we know it today. Instead, people used government coins (metal money) or banknotes, which were pieces of paper issued by (produced by) banks as a promise to pay the person holding the banknote in “real” money – metal coins.

Historically, in most places government-issued paper money had always been backed by, or represented the value of, some amount of precious (valuable) metal, such as silver or gold. But since the government needed money to pay for things to fight the war, President Abraham Lincoln decided simply to print paper money even though the government did not have metal money to back it up. The paper money was instead backed by the trust one had in the U.S. government.

Not surprisingly, the value of this new paper money depended on just how much people trusted the U.S. government. When the war was going badly (not well) for Lincoln and the North, the value of the money declined (went down). When the North was winning, people trusted the government more and the value of these paper bills (pieces of paper money) increased.

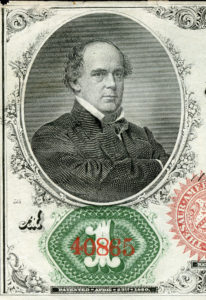

The mastermind (person with the smart or clever plan) behind the printing of paper currency (money of a country) was Salmon P. Chase, then Secretary of the Treasury, the part of the federal government responsible for the country’s money. Chase was also a very ambitious (wanting very much to succeed) politician. To give himself more attention, Chase put his own portrait (image of a person’s face and shoulders) on the United States’ first dollar bill (see photo), called “greenbacks.”

Chase’s greenbacks helped the government avoid financial ruin (complete destruction), but they had a major problem. Because they were produced quickly and weren’t well thought out (planned), it was easy to counterfeit (copy; produce fake versions). By the end of the Civil War in 1865, one in every three bills was fake (not real). At some points during the war, a dollar bill was only worth 34 cents due in part to counterfeiting (100 cents = 1 dollar), although the lack of a gold or silver standard (backing) contributed to this as well.

President Lincoln understood this problem. On April 14, 1865, he created the Secret Service to purge (eliminate completely; get rid of totally) the country of counterfeit bills. Ironically, it was later that same day that Lincoln was shot. The two events were not connected, however.

Today, the Secret Service is mainly known for protecting the president of the United States. But at the time President Lincoln created the Secret Service, it was all about money. It was only 36 years later that the Secret Service was assigned (given the job) to protect the president. By then, there had been two more presidential assassinations: President James Garfield in 1881 and President William McKinley in 1901.

Back to counterfeit money: The Secret Service knew it had an important job to do. If they didn’t stop counterfeiters, the country was in danger of hyper-inflation, which is when prices go up very quickly and people can buy less and less with the same amount of money. The Secret Service used a staff (group of workers) of 10 people, some of whom were reformed (no longer a criminal) counterfeiters themselves, to clean up (to remove the bad or fake) the United States’ currency. By 1869, the Secret Service had arrested over 200 counterfeiters and opened 11 offices across the country.

How much of the United States’ currency today is counterfeit? Only one bill in 10,000 – or at least, that’s what the U.S. government says, if you trust them.

~ Jeff

Mara Abbott could see it.

Mara Abbott could see it. Are you unable to sleep at night because your conscience is bothering you? Your conscience is the feeling you get or the voice in your mind that tells you you’re doing wrong. If your conscience is bothering you, you’re feeling guilty (with a feeling of having done something wrong) about something.

Are you unable to sleep at night because your conscience is bothering you? Your conscience is the feeling you get or the voice in your mind that tells you you’re doing wrong. If your conscience is bothering you, you’re feeling guilty (with a feeling of having done something wrong) about something. Summer is winding down (coming to an end) in the U.S., and Matt Pace is probably glad to see it end.

Summer is winding down (coming to an end) in the U.S., and Matt Pace is probably glad to see it end. )

)