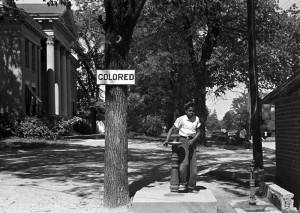

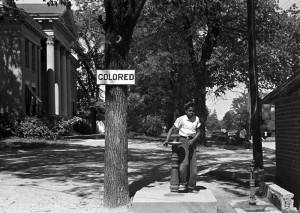

If you lived in the American South in the 1940s and you were African American, you would likely be very aware of the Jim Crow laws (see “What Insiders Know” in the Learning Guide of English Cafe 197). These laws segregated (separated into different groups) white and black Americans, preventing African Americans from going to the same places, using the same services, or having the same rights.

If you lived in the American South in the 1940s and you were African American, you would likely be very aware of the Jim Crow laws (see “What Insiders Know” in the Learning Guide of English Cafe 197). These laws segregated (separated into different groups) white and black Americans, preventing African Americans from going to the same places, using the same services, or having the same rights.

For many people at that time, the issue was black and white (very clear) — literally — and only focused on whether someone was white or black. This meant that there was some ambiguity (uncertainly; not clear distinctions) for people who were neither of European or African descent (origin; background). This ambiguity help some people avoid the harsh (tough; rough) treatment of Jim Crow laws. Take, for example, the Reverend Jesse Wayman Routté. When he visited the American South for the second time, he wore a disguise (clothing and accessories that prevented others from knowing one’s true identity).

The Reverend Routté was a minister (church leader; priest) of a Lutheran church in New York. On a 1943 trip to Alabama to officiate (perform a ceremony, usually a wedding) at his brother’s wedding, he was treated very poorly, like any other African American would expect at that time. Being from the North, Routté wasn’t accustomed to (used to) this treatment and was dismayed (upset). So when he was invited to return to Alabama to visit his brother in 1947, he decided, on the advice of colleagues (coworkers), to wear a turban, a few yards of material wrapped and tied around his head. This, they said, would make things a lot easier.

The turban is worn by many cultures in many different countries, but was not common in the U.S. at that time. If the Reverend Routté was considered foreign — not African American — would his treatment change? That’s what he wanted to find out. Instead of just wearing a simple turban, however, Reverend Routté decided to go all out (do the maximum). He went to a costume (clothing and accessories worn to appear as someone or something else) shop and rented a tall, purple, sparkling (reflecting a lot of light) turban. And when his train was about to arrive in Alabama, he put on the turban and a long robe (a long, loosely-fitting piece of clothing, similar to a coat).

He stepped off the train in his new costume and wore it for nearly the entire week of his visit. He not only saw his family, but wanted to get wider reaction. Although Routté never said he was a visitor from abroad (another country), he was treated like foreign royalty (king, queen, or another member of the royal family) or a foreign dignitary (important representative of a country). He ate in fancy restaurants where African Americans were not allowed to enter, he visited a segregated school and was given a tour, and he even visited a police station, where he was treated deferentially (with respect) and given a tour by the police chief (leader of the police). He also visited important business owners and many other places Africans Americans were not allowed to go. Everywhere he went, he was treated with respect.

Within days of Routté returning to New York, an article appeared in the newspaper recounting (describing) his “experiment” and the story spread across the country. Routté later treated the entire experience as a joke and laughed about it, but other people were not so amused (entertained), including the leaders of his own Lutheran church and important civil rights figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt.

Routté was not the only person who used the turban to avoid problems in the American South at this time, but his experience was one of the most talked about. To find out more about Routté, you can read an article about him here, and to learn about others who also used this “turban trick,” see this National Public Radio story (where you’ll also see a picture of Routté in his turban).

– Lucy

* There is a popular expression, “Clothes makes the man,” which means that people judge others by how they dress and the clothes they wear.

Photo Credit: Segregation 1936 from Wikipedia

(The term “colored” was used to refer to African Americans at that time, but is now considered offensive.)

Get the full benefits of ESL Podcast by getting the Learning Guide. We designed the Learning Guide to help you learn English better and faster. Get more vocabulary, language explanations, sample sentences, comprehension questions, cultural notes, and more.

Get the full benefits of ESL Podcast by getting the Learning Guide. We designed the Learning Guide to help you learn English better and faster. Get more vocabulary, language explanations, sample sentences, comprehension questions, cultural notes, and more.