When Fred (not his real name) turned sixty-five, he retired and did something he had always wanted to do: he returned to school. Fred joined students more than forty years younger than he and began studying for a Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree, the degree that many pastors and priests earn (complete the requirements for) before they begin their work. Most M.Div. degrees require students to learn Hebrew and Greek – the original (at the beginning) languages used to write the Bible – well enough to read them. Fred did, and he earned his degree.

When Fred (not his real name) turned sixty-five, he retired and did something he had always wanted to do: he returned to school. Fred joined students more than forty years younger than he and began studying for a Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree, the degree that many pastors and priests earn (complete the requirements for) before they begin their work. Most M.Div. degrees require students to learn Hebrew and Greek – the original (at the beginning) languages used to write the Bible – well enough to read them. Fred did, and he earned his degree.

Last year, Gary Marcus wrote a book called Guitar Zero. In it he described learning how to play the guitar after he was forty years old. He succeeded and has played for audiences in Brooklyn, New York, where he lives. After his book was published, Marcus discovered that other people had had similar experiences. A journalist wrote to tell him about her seventy-six-year-old father. He had learned to play the guitar when he was older and had recently written her to say that he and two friends had formed a band called “The Three Grandfathers.” An engineer in Portland, Oregon, told him how he had returned to the guitar after he had a heart attack when he was in his sixties (60-69 years old).

Should we be surprised by these stories? Some people would be. Some people believe that you have to start when you’re young if you want to do certain things, like learn a new language or how to play a musical instrument. They believe that the connections in our brains have become permanent by the time we are adults and can’t be changed. If that’s true, you’ll never be able to do these things very well.

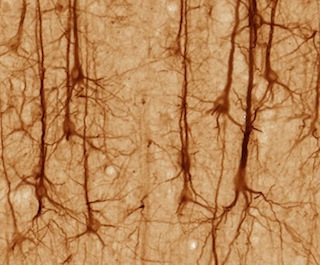

Marcus, a psychology professor at New York University, says that scientific evidence for this belief, called the critical-period theory, is far weaker (less strong) than widely supposed (believed). James Old, a neuroscience (brain science) professor at George Mason University, agrees. He says that the adult mind is “very plastic.” In other words, it can be changed, even when you’re older; old connections can be broken and new ones made. According to Olds, “The brain has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly (while being used), altering (changing) the way it functions (works or operates).” That’s good news, especially for older adults!

Near the end of his book, Marcus makes another point (states another fact or opinion) that applies to (affects) language learners. He points out (tells us) that the process of developing a new skill can bring as much pleasure as accomplishing the goal. This is especially true for language learners because the key to language development is reading and listening – to ESL Podcast, for example – for your own pleasure. More good news!

~ Warren Ediger – English tutor/coach and creator of the Successful English web site.

Photo of neurons courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

New York’s subway system – one of the world’s largest and busiest – was part of a grand (big and impressive) plan that would make it possible for anyone living in the greater New York area (in and around New York City) to go wherever they wanted to go.

New York’s subway system – one of the world’s largest and busiest – was part of a grand (big and impressive) plan that would make it possible for anyone living in the greater New York area (in and around New York City) to go wherever they wanted to go.